In addition to the history of Soviet commemorative practices, I am also interested in post-Soviet war commemoration linked to Victory Day (May 9), the most widely celebrated military-commemorative holiday in the world today. Beyond the former Soviet republics, my research on Victory Day and related practices covers a range of countries that now have sizeable communities of people with a Soviet background, especially Germany.

In 2013 and 2015, I co-directed two large-scale collective research projects on this topic. Our teams—which included sociologists, historians, anthropologists, and others—studied Victory Day celebrations in different locations in the post-Soviet world as well as in other European countries. In addition to ethnographic observation we conducted numerous interviews with organisers and regular participants, took photos, drew maps, analyzed coverage in the press and social media, and conducted archival research. We were particularly interested in how participants interact with the material environment, especially with Soviet war memorials.

This page lists the publications that came out of these projects, in English, German, French, Russian, Ukrainian, and Belarusian. It also collects video and audio recordings of talks, interviews, and discussions. There is no general overview of the projects in English as yet, but I’m currently working on a book on the past and present of Soviet-style war commemoration that will, among other things, summarize our observations. To make this page easier to navigate for English speakers, English-language publications are presented in gray, and videos in English can be found by searching for three number signs (###). Publication dates are in the format most appropriate to the language of the publication, so “9.5.2015” for an article in German means it was published on May 9, 2015, not September 5.

For more background on the projects themselves, please refer to the FAQ section below and to the introductions to our two books.

Books:

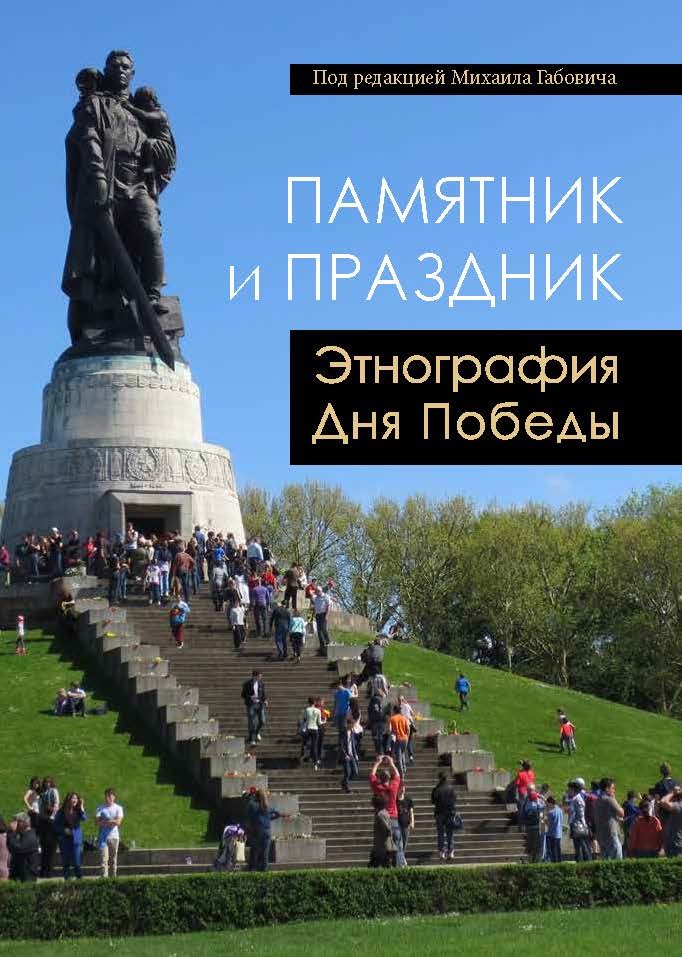

Памятник и праздник: этнография Дня Победы [Monument and Celebration: Ethnographies of Victory Day] / Под ред. Михаила Габовича. Санкт-Петербург: Нестор-История, 2020. – 416 с. 98 цв. илл.

Mischa Gabowitsch, Cordula Gdaniec, Ekaterina Makhotina (Hrsg.) Kriegsgedenken als Event. Der 9. Mai 2015 im postsozialistischen Europa [War Commemoration as an Event: May 9, 2015, in Post-Socialist Europe]. Paderborn: Ferdinand Schöningh, 2017. – 345 S. 38 Fotos, 20 Karten.

Articles, book chapters, interviews:

(All English-language publications are in gray. The final versions of articles marked with an asterisk are collected in the edited volume Памятник и праздник along with previously unpublished texts, such as my own chapter on post-migrant and transnational military commemoration in Berlin.)

- Gabowitsch, Mischa. Are Copycats Subversive? Reflections on the Transformative Potential of Non-Hierarchical Movements. In: Birgit Beumers, Alexander Etkind, Olga Gurova, Sanna Turoma (eds.), The Shrew Untamed: Cultural Forms of Political Protest in Russia. London: Routledge, 2017. P. 68-89.

- Gabowitsch, Mischa. Are Copycats Subversive? Strategy-31, the Russian Runs, the Immortal Regiment, and the Transformative Potential of Non-Hierarchical Movements. Problems of Post-Communism. 2018. Vol. 65. No. 5, p. 297-314. Published online: November 29, 2016.

- Gabowitsch, Mischa, « Commémorer la guerre est un besoin de la société ». Propos recueillis par Fabrice Demarthon. 8.5.2015.

- Gabowitsch, Mischa. „Der Tag des Sieges“. Stuttgarter Zeitung. 9.5.2015.

- Gabowitsch, Mischa. „Die emotionale Bindung verblasst“ [Interview]. Moskauer Deutsche Zeitung. 9.5.2020.

- Gabowitsch, Mischa. „Diesseits der Kremlmauern. Für einen anderen Blick auf die russländische Gesellschaft.“ Mittelweg 36. April/Mai 2017, S. 63-73.

- Gabowitsch, Mischa. „Gedenktage und Militärparaden in Russland zum 75. Jubiläum des Kriegsendes: der 9. Mai und der 3. September von 1945 bis 2020“. Erinnerungskulturen. 6.5.2020.

- Gabowitsch, Mischa.« Le 8/9 mai ». In:Korine Amacher, Eric Aunoble, Andrii Portnov (dir.), Histoire partagée, mémoires divisées. Ukraine, Russie, Pologne. Lausanne : Editions Antipodes, 2020. P. 195-208.

- Gabowitsch, Mischa. « Le 9 mai, Jour de la Victoire. Transformations d’une fête soviétique ». Politika.io. 9.5.2020.

- Gabowitsch, Mischa.“Memory Activism in the Post-Soviet Countries.” In: Jenny Wüstenberg and Yifat Gutman (eds.) The Handbook of Memory Activism. Abingdon: Routledge, forthcoming.

- Gabowitsch, Mischa. [book review] Nikolay Koposov. Memory Laws, Memory Wars. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017. Laboratorium: Russian Review of Social Research 1/2019. P. 186-190.

- Gabowitsch, Mischa. [Rezension] Philipp Bürger. Geschichte im Dienst für das Vaterland. Traditionen und Ziele der russländischen Geschichtspolitik seit 2000. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2018. H-Soz-Kult 2019, 22.3.2019.

- Gabowitsch, Mischa. Research note: Counting visitors to the Treptower Park Soviet war memorial on 9 May (Victory Day) 2014. 10.5.2014. *

- Gabowitsch, Mischa. „Russlanddeutsche und der ‚Tag des Sieges‘ am 9. Mai“ [Interview]. Ostklick, 7.5.2021.

- Gabowitsch, Mischa. „Russland und der Tag des Sieges“. Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, 9.5.2020.

- Gabowitsch, Mischa. „Tag des Sieges”. dekoder. 4.6.2015.

- Gabowitsch, Mischa. „Tag des Sieges: Gegenwart und Zukunft des Gedenkens”. ZoiS Spotlight. 2019. No. 18. 8.5.2019.

- Gabowitsch, Mischa. The politics of Russia’s armed forces day. openDemocracy. 23.2.2017.

- Gabowitsch, Mischa. The present and future of post-Soviet war commemoration. ZoiS Spotlight. 2019. No. 18. 8.5.2019.

- Gabowitsch, Mischa, [film review]. Victory Day (2018), directed by Sergei Loznitsa. Nationalities Papers, Vol. 48 (1), p. 193-195.

- Gabowitsch, Mischa. Victory Day in 2055: Four Scenarios. Free Russia. 9.5.2019.

- Gabowitsch, Mischa. Victory Day: The biography of a Soviet holiday. Eurozine. 8.5.2020.

- Gdaniec, Cordula. „‚Danke Opa! Ich bin in Berlin!‘ Gedenken an den 9. Mai 1945. Postsowjetische Praktiken und Orte”. In: Alexandra Klei, Katrin Stoll, Annika Wienert (Hrsg.), Der 8. Mai: Internationale und interdisziplinäre Perspektiven. Berlin: Neofelis Verlag, 2016. S. 189-209.

- Gdaniec, Cordula. „Rote-Armee-Wald und weiße Flügel am Kliff. Ein Spaziergang durch russische Erinnerungslandschaften in Israel“. Medaon – Magazin für jüdisches Leben in Forschung und Bildung. Bd. 12 (2018), Nr. 22, S. 1–15.

- Hollersen, Wiebke. „9. Mai: Warum Zehntausende am Ehrenmal in Treptow den Tag des Sieges feiern”. In: Berliner Zeitung, 7.5.2021.

- Koleva, Daniela. “The Immortal Regiment and its glocalisation: Reformatting Victory Day in Bulgaria“. Memory Studies, vol. 15, no. 1, February 2022, p. 216-229.

- Makhotina, Ekaterina. „Das Ritual: Der 9. Mai in Litauen als Fest des Sieges und als Europa-Tag“. In: Ekaterina Makhotina, Erinnerungen an den Krieg – Krieg der Erinnerungen: Litauen und der Zweite Weltkrieg. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Rupprecht, 2017. S. 419-432.

- Makhotina, Ekaterina. „Der 9. Mai in Berlin: Gedenkfeier als Protest und Selbstvergewisserung“. Erinnerungskulturen. 13.5.2019.

- Makhotina, Ekaterina. „Der Große Vaterländische Krieg in der Erinnerungskultur“. Dekoder. 2017.

- Makhotina, Ekaterina. „Der Krieg der Toten und der Krieg der Lebenden – Russlands Familien haben ein tieferes Wissen über ‚1945‘, als dem Kreml lieb sein kann“. Neue Zürcher Zeitung. 9.5.2019.

- Makhotina, Ekaterina. „Der Tag, an dem ich nicht gestorben bin“. Neue Zürcher Zeitung. 20.5.2020. Makhotina, Ekaterina. „Ein Fest für wen? Erinnern an den Krieg in Russland“. Erinnerungskulturen. 30.4.2015.

- Makhotina, Ekaterina. „Hinter der Fassade: Der 9. Mai in Russland“. Erinnerungskulturen. 10.5.2017.

- Makhotina, Ekaterina. „Leerstellen – Lehrstätten. Zur Einleitung“. 7.5.2020.

- Makhotina, Ekaterina. „Workshop ‚Kriegsdenkmäler und Gedenkfeiern zum 70. Jahrestag des Kriegsendes‘“. Erinnerungskulturen. 4.5.2015.

- Nikiforova, Elena. “On Victims and Heroes: (Re)Assembling World War II Memory in the Border City of Narva.” In: Julie Fedor, Markku Kangaspuro, Jussi Lassila, Tatiana Zhurzhenko (eds.) War and Memory in Russia, Ukraine and Belarus. Cham: Palgrave, 2017. P. 429-463.

- Pastushenko, Tetiana. “The war of memory in times of war: May 9 Celebrations in Kyiv in 2014 – 2015.” In: Anna Wylegała, Małgorzata Glowacka-Grajper (eds). The Burden of the Past: History, Memory, and Identity in Contemporary Ukraine. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2020. P. 77-90.

- Polukhina, Elizaveta and Alexandrina Vanke. Social Practices of Using War Memorials in Russia: A Comparison between Mamayev Kurgan in Volgograd and Poklonnaya Gora in Moscow. The Russian Sociological Review, vol. 14 (2015), no. 4, pp. 115–128.

- Tytarenko, Dmytro. „‚Der Feind ist wieder in unser Land einmarschiert […]’. Der Zweite Weltkrieg in der Geschichtspolitik auf dem Gebiet der ‚Donecker Volksrepublik’‚ (2014–2016)“. Jahrbücher für Geschichte Osteuropas. Band 68. Heft 3-4. September 2020. S. 508-556.

- Zhurzhenko, Tatiana. “The Soviet War Memorial in Vienna: Geopolitics of memory and the new Russian diaspora in post-Cold War Europe.” In: Patrick Finney (ed.) Remembering the Second World War. London; New York: Routledge 2017, pp. 89-114.

- Барчунова, Т.В. Праздник как событие и ритуал // Сибирский философский журнал. 2017. №1. С. 84-101.

- Браун, Джуди. Перформативная память: празднование Дня Победы в Севастополе // Неприкосновенный запас. 2015. №101. С. 150-165. *

- Ваньке А. В. Наблюдение в поле // Ваньке А. В., Полухина Е. В., Стрельникова А. В. Как собрать данные в полевом качественном исследовании. Москва: Издательский дом Высшей школы экономики, 2020. C. 85-105.

- Габович, Михаил. День Победы: будущее // Кольта. 8.5.2020.

- Габович, Михаил. День Победы: настоящее // Кольта. 7.5.2020.

- Габович, Михаил. Памятник и праздник. Практики празднования Дня Победы в Восточной и Центральной Европе. Большое исследование // Уроки истории. 8.5.2020. *

- Габович, Михаил. Памятник и праздник: этнография 9 мая // Неприкосновенный запас. 2015. №101. С. 93-111. *

- Габович, Михаил. Память и памятники (интервью). Радио Свобода, 8.5.2015.

- Габович, Михаил. Политика и прагматика Дня Защитника Отечества // openDemocracy. 23.2.2017.

- Гусейнова, Севиль. «Победители» в «побежденном» городе: как ленинградцы и одесситы празднуют День Победы в Берлине // Уроки истории. 8.5.2020. *

- Журженко, Татьяна. «Помнит Вена, помнят Альпы и Дунай…»: австрийская и (пост)советская память о Второй мировой войне в городском пространстве Вены // Уроки истории. 8.5.2020. *

- Капась, Іван. Історія дня перемоги: спроба написання // Historians.in.ua. 22.2.2017.

- Касатая, Таццяна. Курган Славы і палітыка памяці: гродзенскія месцы памяці даследавалі ў міжнародным праекце // Hrodna.Life. 25.2.2017.

- Киндлер, Себастьян. Об обращении с советскими захоронениями и мемориалами в Германии // Уроки истории. 8.5.2020. *

- Колева, Даниела. Памятник советской армии в Софии: первичное и повторное использование // Неприкосновенный запас. 2015. №101. С. 184-202. *

- Колягина, Наталья и Наталья Конрадова. День Победы на Поклонной горе: структура пространства и ритуалы // Неприкосновенный запас. 2015. №101. С. 135-149. *

- Кринко Е.Ф., Хлынина Т.П. Памятник на площади: жизнь в тени праздника // Современные проблемы сервиса и туризма. 2014. № 3. С. 27–35.

- Ластовский, Алексей. Идеологическая архитектура Дня Победы: Минск-2013 // Уроки истории. 8.5.2020. *

- Махотина, Екатерина. 9 мая: что происходит за фасадом официоза (интервью). Deutsche Welle. 9.5.2017.

- Махотина, Екатерина. День Победы как поле коммеморативных конфликтов: 9 мая в Вильнюсе // Уроки истории. 8.5.2020. *

- Махотина, Екатерина. Нарративы музеализации, политика воспоминания, память как шоу: Новые направления memory studies в Германии // Методологические вопросы изучения политики памяти: Сборник научных трудов / Отв. ред. А.И. Миллер, Д.В. Ефременко. Москва; Санкт-Петерубрг: Нестор-История, 2018. С. 75-92.

- Махотина, Екатерина. Праздник для всех? Акторы, пространства и практики памяти о Второй мировой войне после 1990 г.Полит.ру, 19.7.2020.

- Махотина, Екатерина. Ритуал 9 мая в Литве как праздник Победы и как День Европы // Преломления памяти. Вторая Мировая война в мемориальной культуре советской и постсоветской Литвы. Санкт-Петербург: Издательство Европейского университета в Санкт-Петербурге, 2020. С. 200-224.

- Пастушенко Т.В. Війна пам‘яти в часи війни: відзначення перемоги над нацизмом після революції гідності // Суспільно-політична активність та історична пам’ять єврейської спільноти в контексті євроінтеграції України. Київ: Інститут політичних і етнонаціональних досліджень ім. І.Ф. Кураса НАН України. С. 233-259.

- Пастушенко Т.В., Титаренко Д.М., Чебан О.І. 9 травня 2014 – 2015 рр. в Україні: старі традиції – нові церемонії відзначення // Український історичний журнал. 2016. № 3. С. 106-124.

- Резникова, Ольга. Скорбь и праздник в (пост)колониальном контексте. Этнографические заметки. Грозный 8, 9 и 10 мая // Неприкосновенный запас. 2015. №101. С. 166-183. *

- Стурейко С.А., Касатая Т.В. Государственный праздник Победы в Беларуси: организаторы и организуемые // Фольклор и антропология города. II (1-2). 2019. C. 289-311.

- Титаренко Д.М. Актуальні проблеми формування джерельної бази з історії Донбасу ХХ-ХХІ століть // Зі стародавності в ХХІ століття: матеріали відкритої обласної краєзнавчої конференції (місто Святогірськ, 04-06 грудня 2015 року). Краматорськ: [б.в.], 2015. С. 30-32.

- Титаренко Д.М. «Враг вновь вступил на нашу землю…»: Велика Вітчизняна / ІІ світова війна в політиці пам’яті на території самопроголошеної ДНР. Частина 1. Historians.in.ua. 22.2.2018.

- Титаренко Д.М. «Враг вновь вступил на нашу землю…»: Велика Вітчизняна / ІІ світова війна в політиці пам’яті на території самопроголошеної ДНР. Частина 2.Historians.in.ua. 1.3.2018.

- Титаренко, Дмитро Миколайович. Досвід війни та пам’ять про війну як чинники. Формування ідентичності населення Донбасу // Філософія. Людина. Сучасність. 2017. Матеріали Всеукраїнської науково-практичної конференції з міжнародною участю, присвячені 80-річчю заснування Донецького національного університету імені В. Стуса (м. Вінниця, 4-5 квітня 2017 р.): тези доповідей / за заг. ред. проф. Р. О. Додонова. Вінниця: ТОВ «Нілан-ЛТД», 2017. С. 133-136.

- Титаренко Д.М. Друга світова / Велика Вітчизняна війна у сприйнятті воєнного покоління Східної України: деякі методологічні аспекти // Південно-Східна Україна: зі стародавності у ХХІ століття: збірник матеріалів ХІ Всеукраїнської історико-кразнавчої конференції учнівської та студентської молоді з міжнародною участю (22-25 листопада 2018 р., Святогірськ). Краматорськ: Донецький обласний центр туризму та краєзнавства учнівської молоді, 2018. С. 6 -10.

- Титаренко Д.М. Политика vs история: К вопросу о трансформации образов Второй Мировой / Великой Отечественной войны в современном украинском обществе // Новое прошлое. 2020. №4. С. 266-280.

- Титаренко Д.М. Свято в тіні нової війни: 9 травня на території «Донецької народної республіки» // Українське суспільство в умовах війни: виклики сьогодення та перспективи миротворення: матеріали ІІІ Всеукраїнської науково-практичної інтернет-конференції,м. Маріуполь, 22 червня 2020 р. Маріуполь: ДонДУУ, 2020. С. 72-77.

- Титаренко Д.М., Титаренко О.О. Воєнний досвід дітей Донбасу: виклик для суспільства // Сучасні суспільні проблеми у вимірі соціології управління. Матеріали ХІІІ Всеукраїнської науково-практичної конференції, м. Маріуполь, 3 березня 2017 р. Маріуполь: ДонДУУ, 2017. С. 225-229.

- Хелльбек, Йохен, Титаренко, Дмитрий. «Мы победим, как победили 70 лет назад наши деды и прадеды». Украина: празднование Дня Победы в тени новой войны // Неприкосновенный запас. 2016. № 4 (108).

- Юдкина, Анна. «Памятник без памяти»: первый Вечный огонь в СССР // Неприкосновенный запас. 2015. №101. С. 112-134. *

Video & audio

Frequently asked questions

What were the project titles? Who directed them? Who funded them?The 2013 project, titled Monument and Celebration: May 9 Celebrations and Interaction Between War Memorials and Local Communities in the Successor Countries to the Soviet Military Bloc, was directed by Mischa Gabowitsch and Elena Nikiforova, with funding from the Franco-Russian Center for the Humanities and Social Sciences and Memorial Moscow. Its results are presented in the Russian-language book Pamiatnik i prazdnik: etnografiia Dnia Pobedy (Monument and Celebration: Ethnographies of Victory Day) edited by Mischa Gabowitsch and published thanks to additional funding from the German-Russian Museum Berlin-Karlshorst.

The 2015 project, titled Victory, Liberation, Occupation: War Memorials and Celebrations for the 70th Anniversary of the End of the Second World War, was directed by Mischa Gabowitsch, Cordula Gdaniec, and Ekaterina Makhotina, with funding from the Remembrance, Responsiblity, and Future Foundation, the Federal Foundation for the Reappraisal of the SED Dictatorship, the Munich-Regensburg Graduate School for East and Southeast European Studies, and the German-Russian Museum Berlin-Karlshorst. The results are published in the German-language book Kriegsgedenken als Event: Der 9. Mai 2015 im postsozialistischen Europa (War Commemoration as an Event: May 9, 2015, in Post-Socialist Europe) edited by Mischa Gabowitsch, Cordula Gdaniec, and Ekaterina Makhotina.

How did the two projects differ from each other?

The first wave was a pilot project. Our shoestring budget did not allow us to dispatch field researchers to locations pre-selected according to a rigid set of parameters. Our team was primarily composed of researchers who had previously studied commemorative practices or had done fieldwork on other topics in the location where they now observed Victory Day celebrations. Thus our sample of cases was essentially dictated by our team’s composition rather than the other way round. At a preparatory workshop we jointly worked out a basic common framework for our research and drew up guidelines for observing, interviewing, photographing, and mapping, but in their book chapters every author wrote about the aspects of the topic that she or he was personally most interested in.

The second project had a stricter research design. The data collection methods were defined more rigidly. We concentrated on a smaller set of countries, but within each country our sample included multiple regions. We had one or several researchers in the field in each region, using a standardized set of guidelines. Their work was supervised by country coordinators, who were also the ones who wrote the chapters for the German volume. In addition, we involved numerous students in the data collection process.

Nevertheless, the second project wasn’t “better” than the first. It would be fairer to say that the two projects allowed us to shed light on different aspects of the commemorative landscape. In the 2015 project we collected more data and obtained a clearer record of certain nationwide tendencies, as well as similarities and differences between regions, in Russia, Ukraine, Belarus, Estonia, and Germany (as well as Moldova, which in the end didn’t make it into the resulting volume for technical reasons). Yet what makes the 2013 project valuable is the individual approach of our authors, each of whom paid attention to themes particularly characteristic of the place they studied.

In addition, the data we collected “before Crimea” and “after Crimea” allow us to note both consistent features of war commemoration and the effects of the political upheaval of 2014.

Is the German volume a translation of the Russian book, or the other way round?

The two books are NOT translations of each other. They are completely different books, NOT two different language versions of one and the same book. The 2017 German book presents the results of the project on Victory Day in 2015. The Russian book documents the project on Victory Day in 2013, but for a number of technical reasons it only came out in 2020; however, earlier drafts of many of its chapters were previously published in the journal Neprikosnovenny zapas (issue no. 101) and on the website Uroki istorii. The authors of the chapters in the two books are also different. The only exceptions, other than myself, are Ekaterina Makhotina (who wrote the chapter about Vilnius for the Russian book and co-authored the introduction to the German book) and Anna Yudkina (who wrote about the first Eternal Flame in the USSR for the Russian volume and co-authored the chapter on Russia in the German book). Except for a few paragraphs in my chapters about Berlin, the texts of the two books do not overlap.

Have the projects been completed?

As part of the two projects, we collected huge amounts of data: over 800 interviews, thousands of photos, hundreds of articles from print and online media, field notes, maps, profiles of individual monuments, etc. Only a small part of these data made it into our books and other publications. Two important aspects that particularly merit further development are cross-country comparison and the historical evolution of Victory Day, both of which are a prime focus of the book I am currently writing in English. For a number of ethical and legal reasons I cannot freely share the data we collected with those who were not part of our projects. However, I’m open to collaborative projects and welcome any questions or ideas for further analysis: just e-mail me.